The mysteries of the Falsified Medicines Directive - where is the logic on safety features?

This article was originally published in SRA

The European Commission says that pharmaceutical companies whose products are not covered by the Falsified Medicines Directive will be prohibited from applying safety features on a voluntary basis. This, Peter Bogaert and Cynthia Burton argue, is contrary to the aims of the directive – to protect public health.

One of the tools selected under the EU Falsified Medicines Directive (Directive 2011/62/EU)1 to address the serious threat to public health posed by falsified medicines is the obligation to apply – in principle – safety features to all prescription-only medicines and to non-prescription medicines if they are at risk of counterfeiting. Delegated acts expected this year will list, if necessary, prescription-only medicines that are exempted from the obligation and non-prescription (ie over-the-counter or OTC) medicines that are subject to it.

The question of which products should be required to carry safety features initially was a contentious one but a broader consensus seems to have developed that all prescription medicines, including generics, should carry them, subject to very specific exceptions. Conversely, only very few OTC medicines should be obliged to carry the safety features..

Complicating matters is the fact that the European Commission has said repeatedly that adding the safety features on a voluntary basis is not allowed under its interpretation of the directive. This article puts the case for allowing voluntary application of the safety features and argues that the commission's position lacks logic and undermines the fundamental stated aim of the directive – to protect public health.

Background

The Falsified Medicines Directive (amending Directive 2001/83) was adopted in 2011 to address a serious public health threat. The recitals to the directive state:

(2) There is an alarming increase of medicinal products detected in the Union which are falsified in relation to their identity, history or source. Those products usually contain sub-standard or falsified ingredients, or no ingredients or ingredients, including active substances, in the wrong dosage thus posing an important threat to public health.

(3) Past experience shows that such falsified medicinal products do not reach patients only through illegal means, but via the legal supply chain as well. This poses a particular threat to human health and may lead to a lack of trust of the patient also in the legal supply chain.

The safety features comprise (i) serialization through a unique identifier for each package, and (ii) anti-tampering devices.

Although the wording of Article 1(11) of Directive 2011/62, inserting point (o) in Article 54 of Directive 2001/83, could at first sight suggest that the term “safety features” only covers the unique identifier and not the anti-tampering device, the fact that the term is used in plural must mean that it also covers the latter. This is clearly the intention as shown by recital 11 (“…safety features should allow verification of the authenticity and identification of individual packs, and provide evidence of tampering”) and by the new Article 47a of Directive 2001/83, which requires parallel importers to apply equivalent safety features “equally effective in enabling the verification of authenticity and identification of medicinal products and in providing evidence of tampering…”.

The obligation relating to the safety features will apply three years after the adoption of the delegated acts that define the unique identifier and its use. These delegated acts will also list, if necessary, prescription-only medicines that are exempted from the obligation and OTC medicines that are subject to it. The delegated acts are expected to be adopted in the course of 2015.

The discussions over whether pharmaceutical companies can on a voluntary basis apply safety features is particularly relevant for OTC medicines that are not brought under the legal obligation and for prescription medicines that are exempted from the obligation. As the purpose of the directive is to protect public health, the logical answer would be that this is possible and should even be encouraged. Such voluntary use can only further contribute to the protection of public health.

Surprising EC position

The European Commission seems to be clearly opposed to voluntary use of safety features. It has stated its views in various meetings on the implementation of the directive:

COM confirmed its position on the voluntary use of safety features, i.e. that it is not possible according to the legislation.2

COM explained that in its view the FMD does not permit voluntary use of the safety features (…"shall not bear the safety features…").3

Medicinal products not subject to prescription shall not bear the safety features, unless they have been listed by the Commission in a delegated act … and

The EU-scope of the unique identifier is non-optional: a medicinal product which falls within the scope must bear the unique identifier. A medicinal product which falls outside the scope must not bear the unique identifier. Thus, there is no 'optional scope' for manufacturers: A manufacturer cannot decide to apply the unique identifier to medicinal products which do not fall within the scope of the safety feature.4

This interpretation is based on the wording of the new Article 54a of Directive 2001/83, which states “[m]edicinal products not subject to prescription shall not bear the safety features referred to in point (o) of Article 54” (unless for OTC medicines that are made subject to the obligation through a delegated act, or where member states use their powers to extend the safety features requirement pursuant to Article 54a (5)).

This narrow technical interpretation is not justified. The wording "shall not" does not seem to have been intended to prohibit voluntary use of safety features as there is no evidence in the legislative history of the directive of such intention. In addition, some language versions of the directive used more flexible wording, especially the German version referred to “müssen nicht” ("do not have to"). The divergence between the different versions is relevant as the English version of the directive is not of higher value, even if de facto the wording of the directive was mainly discussed in that language during the legislative process5. Nevertheless, the commission requested the German version be changed so as to ensure “the alignment of all official language translations to the [English] text”. Such an approach is not legally justified in view of the basic EU law principle that each language version of the directive is authentic.

Instead, when there are interpretation problems, the real meaning of the text must be determined on the basis of the general scheme of the rules and the underlying intention. This clearly veers towards allowing voluntary use of safety features as they provide additional safety safeguards and serve the main purpose of the directive, namely to protect public health. The impact assessment report itself recognizes that the exclusion of OTC medicines from the scope of the obligation reduces the efficacy of the protective measures (“counterfeit OTC medicines may still be toxic, i.e. posing a risk to human health” and “there is a risk that the exclusion of OTC drugs might simply divert illegal activities into that sector”) but on balance the commission proposed the exemption based on cost considerations6. The rules were further refined during the legislative process to allow specific OTC medicines to be brought within the obligation, but this does not change the underlying reasoning. In fact, it confirms it.

Corrigenda published in August 2014

In early August 2014, corrigenda to nine language versions – the German, Estonian, French, Lithuanian, Dutch, Slovakian, Slovenian, Finnish and Swedish versions – of the directive were published in the Official Journal7. In six language versions, the wording of Article 54a is changed so as to make it clearer that voluntary use of safety features is not possible. For instance, the German wording “müssen nicht” (do not have to) is changed into “dürfen nicht” (must not). This clearly is an attempt to bolster the restrictive interpretation that excludes voluntary use of safety features.

The document from the Council of the EU on the corrigenda indicates that they relate to “obvious errors” in the original text (as signed) in more than two languages. This procedure normally requires a more extensive review, but the council register of documents does not seem to contain any such examination (and in general very little information is made public with regard to the corrigenda). In addition, the revision of Article 54a goes beyond “obvious errors” and in reality constitutes a substantive amendment. The legality of the corrigenda is thus doubtful.

Anti-tampering devices

As mentioned, the safety features consist of the unique identifier and anti-tampering devices. The unique identifier is new and requires a fully harmonized approach and an extensive system for checking in and checking out numbers. This will be laid down in the delegated acts. Anti-tampering devices, on the other hand, are not new and operate independently (merely by being applied to the packaging). The directive also does not require them to be regulated.

In response to a 2008 consultation, EU R&D-based pharmaceutical industry group EFPIA identified the following examples of anti-tampering devices8:

Companies have therefore developed as part of their respective anti-counterfeit strategies, a number of tamper evident container closure systems. These include:

- Tamper evident security seals and tapes that break and leave a visible trace when someone first opens the pack;

- Packaging techniques with perforated boxes, which must be ripped in order to open the box. This allows the option to close up the box once it has already been opened while still making any initial tampering evident;

- Special glue for the flaps, which must also be ripped open but which does not allow the box to be closed again. However, this is often combined with perforated flaps.

If the structure of the pack is compromised (flaps ripped or unglued, seal broken), it becomes evident to the end user that tampering has occurred prior to consumption, which serves as a way to notify the end user that the product may be sub-standard and/or counterfeit and is therefore at risk. These packaging techniques therefore help to guarantee the integrity of the pack’s content. This is in fact already currently widely applicable to many common consumer products such as food packages found in supermarkets.

Similarly, in the UK, the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry provided the following examples during the same consultation exercise9:

Other packaging technologies in use include

- Tamper evident security seals that self destruct and leave a visible trace when someone first opens the pack.

- Packaging techniques with perforated flaps, which must be ripped in order to open the box. This allows the option to close up the box once it has already been opened while still making any initial tampering evident.

- Special glue for the flaps, which must also be ripped open but which does not allow the box to be closed again.

Form over substance

It is hard to follow the commission’s interpretation. It directly undermines the objectives of the directive, and more broadly of the medicines rules in general. It also contravenes the general requirement under Article 168 of the Treaty of the Functioning of the EU that the EU legislation must “set[...] high standards of quality and safety for medicinal products” so as to ensure “[a] high level of human health protection.”

By interpreting the rules in an unnecessarily strict manner, the commission forces pharmaceutical companies to go backwards on safety guarantees where certain anti-tampering devices are already being used. And this would apply to medicines, which are the most sensitive products from a public health point of view, and not to medical devices, foods and cosmetics.

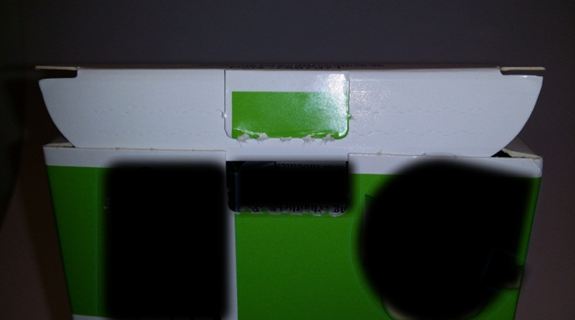

Indeed, why will a perforating system for an OTC medicine as shown in Picture 1 below be prohibited as from 2018 while an almost identical mechanism will remain permitted for medical devices, such as the example shown in Picture 2 and for foods, cosmetics and other consumer products?

Picture 1.

Picture 2.

The same considerations of course also apply to the voluntary use of the unique identifier. This can also not be easily addressed by bringing certain OTC medicines under the mandatory scope of the safety features. Such amendment requires a delegated act, which requires careful preparation and examination and could, according to the commission, take many months, if not years.

The French have a saying that le ridicule ne tue pas, which literally translated means "The ridiculous does not kill". Unfortunately, this may be an area where the saying is not accurate. The commission stated in the above mentioned impact assessment report that public health consequences of counterfeiting medicines “can be considerable” and “include death, additional medical interventions, and prolonged hospitalisation and long-term disabilities (e.g. after strokes, loss of hearing)”.

There is still time to correct the situation. The new principles will only apply three years following the publication of the delegated acts on safety features. This will probably be in 2018. That time should, however, be used effectively to avoid negative health consequences.

References

- Falsified Medicines Directive (Directive 2011/62/EU of 8 June 2011 amending Directive 2001/83/EC), OJ, 1 July 2011, L174/74-87, http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol-1/dir_2011_62/dir_2011_62_en.pdf

- Draft summary of the Stakeholders Workshop, 28 April 2014, SANCO/TSE/fm/ddg1.d.6(2014)

- Draft summary of the Stakeholders Workshop, 6 December 2013, SANCO/TSE/ab/ddg1.d.6(2013)4026513

- Commission document of 31 October 2013 for the third meeting of the expert group on delegated act on safety features, SANCO/PT/ab/ddg1.d.6(2013)3631210

- Email of 2 February 2014 - copy on record

- Impact assessment report, 10 December 2008, SEC(2008) 2674, pp 42 and 67, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=SEC:2008:2674:FIN:EN:PDF

- OJ, 9 August 2014, L238/31, in the respective languages versions

- EFPIA response to the European Commission public consultation in preparation of a legal proposal to combat counterfeit medicines for human use, 9 May 2008, http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/counterf_par_trade/doc_publ_consult_200803/114_efpia_en.pdf

- ABPI response to the public consultation in preparation of a legal proposal to combat counterfeit medicines for human use -- key ideas for better protection of patients against the risk of counterfeit medicines, undated, http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/counterf_par_trade/doc_publ_consult_200803/36_british_pharmaceutical_industry_en.pdf

Peter Bogaert is a partner and Cynthia Burton is an associate with law firm Covington & Burling LLP. Both are based in Brussels, Belgium. Emails: [email protected] and [email protected].