FDAAA Impact Analysis (Year 4): The REMS Retreat Continues - For Now

This article was originally published in RPM Report

Executive Summary

As the fifth year of the REMS era begins, FDA is imposing mandatory programs less frequently than it did even in the first year after the law creating formal risk management plans took effect. But there are some new trends to watch, including the evolution of REMS classes and the emergence of products with REMS-in-waiting.

FDA’s use of the Risk Evaluation & Mitigation Strategy authority declined for the the third consecutive year. That is a remarkable trend, considering that the REMS have existed for just four years.

The Food & Drug Administration was granted the formal authority to impose post-marketing risk management plans under the FDA Amendments Act of 2007, with the relevant portions kicking in in 2008. The RPM Report has tracked use of the new tools since then, looking at the agency’s use of the REMS authorities and mandatory post-marketing study authorities every six months.

The latest data underscore the very different dynamics in the agency’s use of the two new tools.

The use of mandatory post-marketing studies began as a fairly common practice, especially for new molecules, and has continued at that level. Four years after FDAAA took effect, approximately three-quarters of all new molecules approved had at least one mandatory post-marketing trial requirement, as did roughly 40% of all NDAs classified by the agency as “original” approvals.

Those numbers have fluctuated a bit from year to year, but there is no obvious sign that FDA is invoking that authority much more or much less as time passes.

In contrast, the use of REMS ramped up quickly and has fallen off just as fast. That trend has been apparent for two years, but the most recent six-month period makes it crystal clear. (Also see "REMS Use Declining, But Post-Marketing Requirements Remain" - Pink Sheet, 1 Nov, 2011.)

By almost every metric, FDA’s use of the REMS authority in the most recent six months has been at the lowest level since the law took effect. Only one of the 13 new molecular entities approved by FDA between October 2011 and March 2012 (Affymax Inc.’s peginesatide brand Omontys) was approved with a REMS. Of the 52 NDAs classified as “original” approvals by the agency, just 6 had a REMS.

That 11% rate of applying REMS to original NDA approvals marks the fifth consecutive period where the risk of a REMS has declined (from a peak of more than 40% of original NDAs approved between April-September 2009).

The reasons for the drop-off are fairly clear:

- FDA’s decision in Februay 2011 that the imposition of a consumer medication guide does not in fact trigger a mandatory REMS. (Also see "FDAAA Impact Analysis (Year 3): REMS R.I.P.? Not Yet" - Pink Sheet, 1 Jun, 2011.)

- The significant feedback from across the health care system about the unintended consequences of REMS. That pushback continues, and includes a recent presentation to the agency’s Drug Safety Oversight Board from the Department of Defense on some of the unintended consequences of REMS.

- The continued and readily acknowledged uncertainty within FDA about the value and impact of specific REMS strategies. No one in the agency is ready to argue that they can predict when or how a REMS is going to make a meaningful difference in patient outcomes. That may be encouraging greater focus on analyzing the impact of existing REMS rather than pushing ahead with new ones.

However, it would be premature to declare the REMS era over before it really began.

FDA is using REMS less frequently—but when it uses them, they are more impactful.

In addition, there appears to be little chance of FDA backing off from REMS in classes where they have already been established. Rather, those are the areas where new REMS are being imposed, creating—if you will—a new distinction among therapeutic classes: those with REMS and those without.

Last but not least, there may be an emerging class of drugs—call them REMS-in-waiting—where no REMS is required upon approval, but the groundwork is set to impose a REMS very quickly with additonal post-marketing experience.

MedGuide-Only REMS Not the Only Change

The dramatic drop-off in use of REMS is partly explained by FDA’s decision 15 months ago not to impose a REMS in every case where a MedGuide is mandatory. Indeed, at least three of the original NDAs approved in the past six months were originally submitted with REMS, but FDA informed the sponsors that a REMS would no longer be required because of that change in policy.

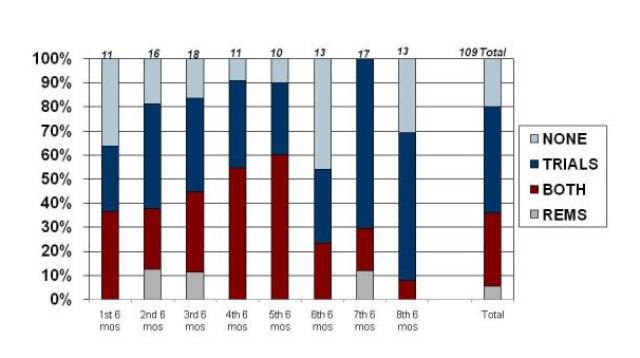

That impact is seen clearly in the trends for use of REMS with new molecules, where the use peaked at 60% in the class of drugs approved between April-September 2010. In the past six months, that use dropped to below 10%, just one out of 13 NMEs approved. Post-marketing study requirements, on the other hand, continue to be imposed on roughly three-quarters of new molecules.

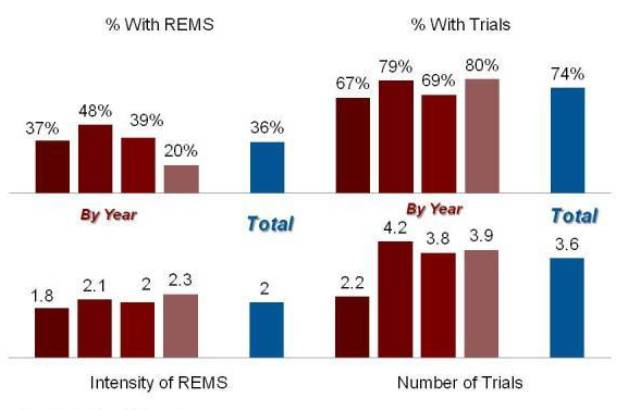

Exhibit 1

FDAAA Impact: New Molecules

Source: Prevision Policy LLC, The RPM Report

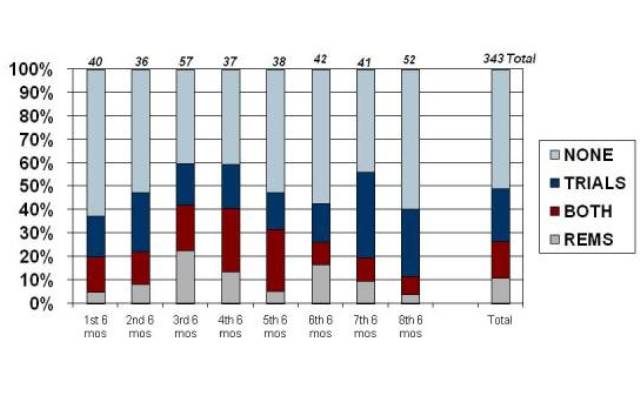

For all of the “original” applications approved by FDA—a category that includes NMEs but also new formulations, new combinations, etc.—the peak use of the REMS authority actually came a year early, in the class of products approved between April and September of 2009. FDA imposed a REMS on more than 40% of the products approved in that period, a rate that has declined steadily since then to just about 10% of the latest cohort of approvals.

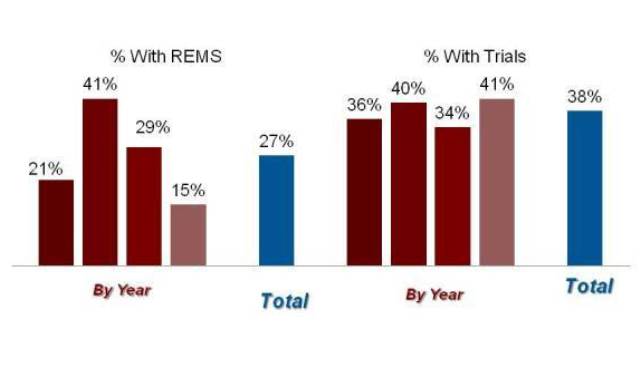

Exhibit 2

FDAAA Impact: Original Approvals

Source: Prevision Policy LLC, The RPM Report

As that data suggests, the dropoff in REMS isn’t just a function of the new policy related to the intersection between REMS and mandatory medication guides.

Even without the “MedGuide-Only” REMS, the agency’s use of the new authority has dropped sharply—though not below the levels seen when the program was new.

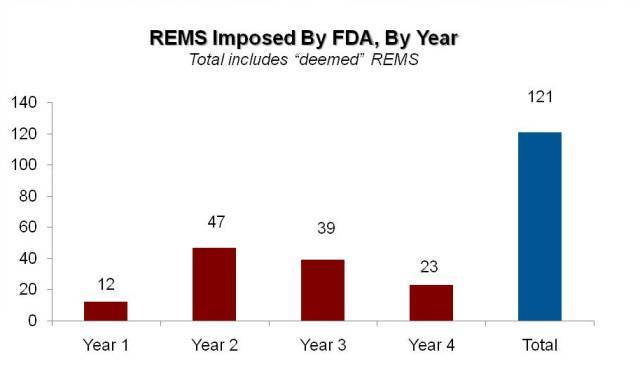

By The RPM Report’s analysis, FDA imposed 12 REMS that included more than a MedGuide in the first year of the new authorities, which jumped to 47 in the second year. That number has declined since, with 39 new REMS imposed in year 3 and just 23 in year 4. (The numbers in the more recent years are inflated somewhat by the timing of FDA’s coversion of a handful of pre-FDAAA risk management programs to REMS—the so-called “deemed” REMS.)

Exhibit 3

The "Real" REMS Trend

Source: Prevision Policy, LLC; The RPM Report

So by almost every measure, the use of REMS continues to decline.

Almost—but not all.

There are at least two important ways in which FDA’s use of the REMS authority can still be judged to increase.

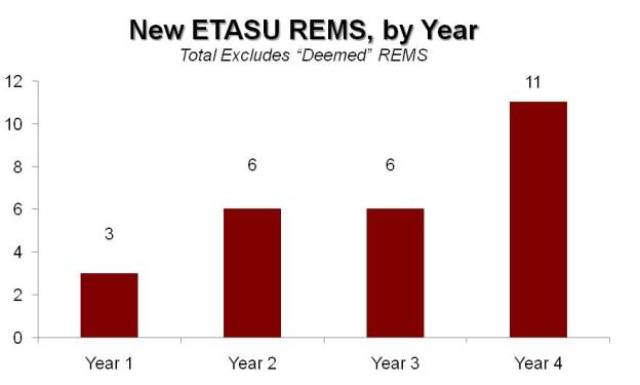

First, the agency is clearly using the more restrictive programs—those with conditions defined in statute as “Elements to Assure Safe Use” or ETASU—with increasing frequency as the years go by. Those programs are still relatively uncommon, but FDA is turning to this tool in a growing number of situations.

Exhibit 4

Restrictive REMS Still Increasing

Source: Prevision Policy LLC, The RPM Report

FDA imposed just three new ETASU REMS in the first year. That doubled to six in each of the next two years, and then nearly doubled again to 11 in the fourth year. Those are small numbers to be sure.

But, by way of comparison, FDA identified only 16 risk management programs that pre-date FDAAA that met the statutory standard to be “deemed” a REMS, using a definition that essentially matches the ETASU definition.

So the agency has imposed 27 new programs with Elements to Assure Safe Use in the four years of the FDAAA era after using analogous risk management tools just 16 times in the agency’s history prior to 2007. (Or, more fairly, over the prior decade when FDA began to experiment with risk management plans as an option for drugs with unique benefits and significant toxicity.)

To summarize, the agency is using REMS less frequently now than it did two or three years ago—but the impact of the typical REMS is much greater. The RPM Report attempts to measure the burden of the REMS authority using an “intensity” score, basically a four point scale classifying a REMS as a level 1 (MedGuide and Assessment Only), 2 (Communication Plan), 3 (ETASU but not an implementation system) or 4 (ETASU with implementation plan/restricted distribution).

For new molecules at least, the average intensity of each REMS has continued to increase, with the median score now 2.3, meaning that most REMS include ETASUs.

Exhibit 5

The REMS Dashboard: NMEs

Source: Prevision Policy LLC, The RPM Report

Exhibit 6

The REMS Dashboard: All Original Approvals

Source: Prevision Policy LLC, The RPM Report

REMS Get Class-y

There is a second dimension in which FDA’s use of REMS could be considered to be increasing: the number of products affected goes up much faster than the number of REMS programs suggests.

The RPM Report’s count of new REMS treats class-wide “shared” programs as a single instance. So, among the 11 ETASU REMS imposed in the fourth year of the program, the agency’s program for transmucosal immediate-release fentanyl (TIRF) products counted only once, even though it applies to seven different brands. (Also see "Transmucosal Fentanyl Products Become First Plug-and-Play REMS" - Pink Sheet, 1 Feb, 2011.)

That program will be dwarfed by the proposed shared REMS for long-acting opioids, which is still being finalized by FDA. That single program will apply to two dozen brands. (Also see "Regulatory Alchemy: The Transformative Power of the Opioid REMS" - Pink Sheet, 1 Jun, 2011.)

On the other hand, many of those agents have already been approved with stand-alone REMS and are counted in the current data.

In fact, one way to summarize FDA’s current use of REMS is that they are largely limited to classes where REMS were imposed already. The one new molecular entity given a REMS in the last six months—Omontys—fits that model, since it is a new entrant in the ESA class where Amgen Inc.’s Epogen and Aranesp and Johnson & Johnson’s Procrit are already subject to a REMS imposed after much deliberation and controversy. (Also see "The Rebirth of A Niche Product: Three Silver Linings on the ESA REMS" - Pink Sheet, 1 Feb, 2010.)

Other newly imposed REMS include several for different opioid formulations, one for Amylin Pharmaceuticals Inc.’s GLP-1 inhibitor Bydureon, where Novo Nordisk Inc.’s Victoza REMS is already a model, and one for J&J/Bayer AG’s supplemental indication for Xarelto in the anticlotting class, where all new entrants are being required to have communication plans (and where Xarelto already had one for its prior indication).

The thinking of REMS in class-wide terms is also posing significant complications for the agency. In two very different high-profile contexts, FDA is wrestling with a strong desire to impose a REMS on an ingredient in one circumstance even though there is no REMS on the ingredient for other uses.

In the case of Vivus Inc.’s Qnexa, FDA is concered about a teratogenicity risk associated with the topiramate ingredient in the weight loss combination—but also unwilling to limit access to topiramate for its already approved uses in epilepsy and migraine prophylaxis. (Also see "Setting the Stage: Qnexa and the Power of REMS" - Pink Sheet, 1 Mar, 2012.) For Gilead Sciences Inc.’s AIDS combo Truvada, the issue is expanding use into pre-exposure prophylaxis—where there is a clear need for enhanced education—without limiting access for the existing HIV treatment population. (Also see "Two Indications, One REMS: FDA Panel Debates Restricted Access For Truvada In PrEP" - Pink Sheet, 21 May, 2012.)

The latest batch of approvals includes an interesting precedent in the opposite direction: FDA approved the drug mifepristone for a new use in Cushing’s syndrome, and told the sponsor, Corcept Therapeutics Inc., that a proposed REMS would not be necessary for the Korlym brand. Mifepristone is already marketed under a restricted distribution program for its other approved use as an abortifacient, where it remains better known as RU-486.

REMS in Waiting?

The agency’s increasing unwillingness to apply the REMS in virgin territory may be creating a new class of drugs: those approved with a REMS-in-waiting.

Roche/Genentech Inc.’s basal cell carcinoma therapy Erivedge (vismodegib) looks like a poster child for this new class of drugs.

The drug cruised through FDA based on strong efficacy data and joined the recent trend of breakthrough oncology therapies gaining approval well ahead of the six-month priority review deadline.

However, there was some behind the scenes dialogue within FDA about how to manage a clear safety risk: teratogenicity associated with vismodegib. The risk was clear enough that Genentech submitted a proposed pregnancy prevention program as part of the NDA filing on September 8, 2011. During a consult review, the Division of Risk Management concluded that a REMS would be appropriate, albeit one that took an education/registry approach rather than a more restictive pregnancy prevention model.

The clinical review team in FDA’s Office of Hematology & Oncology Products, however, came to a different conclusion, based primarily on the concern about setting a precedent. Many other cancer drugs are real or potential teratogens, the division reviewers noted, and oncologists understand how to manage the risks of pregnancy exposures.

The different perspectives were aired during a regulatory briefing on December 9. The internal meeting with senior managers—kind of an “internal” advisory committee at FDA—ended with the senior managers siding with the new drugs group in this case, and that view was reflected in the final approval memo by Division Director Patricia Keegan.

The Division of Risk Management accepted that conclusion, but somewhat grudgingly.

“While not in full agreement, DRISK aligns with the advice provided by the Regulatory Briefing panel and the decision [the review division] has made to approve vismodegib without a REMS based upon the conclusions reached by the FDA pharmacology and toxicology review team and on the existing regulatory precedent for managing the risk for teratogenicity in oncology drugs,” safety reviewer Amarilys Vega wrote.

“However, DRISK has a low threshold for re-evaluating the need for a REMS for vismodegib, particularly if the treated patient population expands or if new safety data become available indicating that product labeling alone is not effective at managing vismodegib’s risk of teratogenicity,” she wrote.

In addition, “DRISK recommends strong labeling regarding the teratogenic risk and requiring postmarketing pregnancy exposure data collection and analysis under a postmarketing requirement (PMR). The pharmacovigilance plan section of the Pregnancy Prevention Program included in Genentech’s original risk management proposal provides a reasonable framework for the development of a PMR.”

Those conclusions offer a good touchstone for judging the current low rate of REMS use by the agency.

For now, FDA is willing to approve products without REMS and trust to the judgment of experienced clinicians (especially of the clinicians are part of a well-defined specialty segment of medicine).

- But in the face of rapidly expanding use and/or new safety information, a REMS is likely to be a next step.

- And that new safety information just might be fed from a post-market study required as a condition of approval.

The use of REMS may be trending sharply down, but those are some strong reasons to believe that the REMS era really is just beginning.