How Pharma is Working to Change Cultures With Q10 Quality Systems

This article was originally published in The Gold Sheet

Even the most highly regarded drug manufacturers can become complacent, allow their attention to wander, and the next thing they know, FDA is telling them their quality has spiraled out of control.

They pay the price with FDA, they replace their management teams, they invest in new equipment, facilities and systems – and they vow never to let quality stray again.

And yet just when they're certain they've got it back under control, off it goes again.

Wouldn't it be nice if there were a way to avoid these cycles?

Juan Andres, head of quality at Novartis Group, has been working on an answer to that question. "Most companies realize the need of that cultural change when they get in deep trouble and sometimes that is the value that regulators bring. They put you at the edge and then you make that change," he told a recent conference in Arlington, Va.

"The challenge for us is to start identifying the need for change differently, before somebody else does the job for us or pushes us to go into it. That takes guts, and we are fighting against inertia," Andres told an Oct. 4-6 meeting of pharmaceutical quality professionals at the Crystal Gateway Marriott in Arlington, Va.

"We need to be able to articulate and to be able to catalyze that mindset and that cultural change in our organizations with the business leaders prior to being punished, or punishing the patients out there with these problems."

This October gathering, repeated last month in Brussels, was organized by two industry associations, the Parenteral Drug Association and the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering, and two regulatory agencies, FDA and the European Medicines Agency.

The meeting focused on Q10, the quality systems guideline that the International Conference on Harmonization produced in June 2008 to hold senior management responsible for quality, and to promote continual improvement of pharmaceutical manufacturing processes, products and quality systems.

The intent was to explore what Q10 says and how to implement it, based on case studies. A major focus of the conference turned out to be the problem of how to manage corporate quality cultures.

How Lilly started listening

Frank Deane, Eli Lilly & Co.'s president of global manufacturing, told the story of Lilly's quality crisis, and how, with FDA's help, the company emerged from a fog of complacency.

It started with a couple of major FDA inspections of Lilly's parenterals plant in Indianapolis in early 2001, each generating some 50 observations.

That's when Lilly asked Deane, who'd been working in API manufacturing, to take over as the company's head of quality.

"We did a lot of remediation, we thought we had fixed problems, then we had a major inspection in October that really raised considerable other issues as well," Deane said.

Looking back on it two years later, an FDA compliance director told Deane, "'I don't think the word 'denial' does full justice to where Lilly was back in 2001."

Not comprehending the intent of the Form 483 reports, the company responded by focusing on each individual inspectional observation, he said. "So we weren't listening to what the agency was asking us about. … The overarching observation for all three 483s was really about the effectiveness of the quality control unit."

He recalls an FDA compliance manager explaining it to him this way: "Dr. Deane, put aside all the observations. We can talk about that in detail. But really the overarching concern is when our investigators go into Lilly's plants, they don't see a state of continuous improvement. That's the essence of the concern."

"That was very traumatic for me because I'd been 20 years with Lilly in manufacturing and quality at that point, and obviously we weren't getting it right," he said. "Whatever I'd been doing, I thought I'd been doing the right things, and many other people, but we had missed something, so that led to a lot of introspection."

Deane's first lesson from this process was to "look beyond the observations, really listen." Take notice, he said, if people are rushing batches late on Friday afternoons, if the quality unit is stressed out, if instead of improvement, annual quality reviews show you are "like a duck paddling frantically, trying to keep pace all year."

Understanding and accepting FDA's criticism turned out to be the hardest part of the process, Deane said. "We're a very proud firm. We're a family firm, isolated in a sense. It was very hard for us to really listen. Once we listened, it was really easy. Once we accepted there was a problem, we went about fixing it. But actually listening and internalizing it was quite difficult."

Another lesson learned: don't shoot the messenger. "I remember back in, it was '02, a very painful day … I was over with my boss, reciting the saga of the things that had gone wrong, and he said, 'Frank, this is intolerable.' And he happened to be head of HR of global manufacturing. He said, 'We need to fire people. Fire the Q manager, fire the site head, I don't care. I'm not going to the CEO without saying we took some action on this.'

"I remember kind of smiling and laughing to him. I said, 'You know, if we're going to start shooting people, we probably should start in this office.'

"I said, 'You can shoot the people that are standing there right now. Maybe they're not the best people. But these things didn't happen overnight. They're systemic failures, and you've got hardworking people trying to fix them. So we need to fix the system rather than necessarily shoot the people.'"

Lilly's North Star

Lilly's cultural journey began in 2003 as remediation concluded and the company agreed with FDA on a voluntary quality improvement plan.

At the heart of the plan was a diagram of concentric rings, each labeled with goals. At the center was a small circle inscribed with the phrase, "Making Medicine."

"We called it our North Star," Deane said. "We were 120 years in existence and very proud of our history and obviously making medicine, and many valuable medicines. But we really had to re-ground ourselves in that," he explained.

Major improvements flowed from that initiative. There were leadership changes and reorganizations. Quality, which had been subservient to manufacturing, became its equal and eventually won a seat on the company's executive committee, held by Fionnuala Walsh, senior VP, global quality. Deane represents manufacturing on that committee.

Deane said the quality organization in many pharmaceutical companies does not reach into senior management, "and if that's not right at that level, it's probably not right down all the organization."

There was lots of training. Lilly spent $20 million to convert an older site into a manufacturing and quality training center. And there were substantial capital investments, including $400 million on IT systems and $250 million for upgrades to the Indianapolis parenterals plant that had triggered the crisis. There were also technical improvements, integrated standards and governance processes. "Really what we were doing was actually building a quality system. We didn't fully understand it at the time."

Although a lot of money went into establishing Lilly's quality system, it produced a lot of savings as well, Deane said. "What's the price of quality? Really, quality is free."

The quality system has since proved its preventive value. In 2010, the system began signaling what might have been random quality issues – or the start of a downward trend. The CEO asked them to look into it. It turned out that in anticipation of October's Zyprexa patent loss, the company had allowed staffing to thin out too much in certain areas.

"It's a time when cost control and all the other things are in place," Deane said. "But we got a clear message. If we needed to add people to get this right, that was OK. It was the first, in my head, really true test that we walked the talk."

Crisis at Schering-Plough

The same year that Lilly came under FDA's close scrutiny, so too did Schering-Plough Corp.

Richard Bowles had just joined the company as head of quality after working 27 years at Merck, which later acquired Schering. "Just as I arrived there, there was a series of inspections, repeat inspections," that led to a consent decree, the most onerous consent decree at the time.

Among the features of the settlement was a record $500 million fee to "disgorge" Schering-Plough of any profits it might have made by scrimping on quality.

Bowles told the Q10 meeting about "how we used that … court-ordered quality improvement plan for organizational transformation." The consent decree became an agent for culture change.

FDA's observations concerned quality unit effectiveness, process validation, failure investigations and training, "very, very fundamental areas of compliance," he said. "Because these concerns were identified at multiple manufacturing sites, the logical conclusion was that the quality systems underlying those failures were flawed, leading to a consent decree and leading to a large emphasis on improving those quality systems."

But before it could strengthen its quality systems, the company would have to establish some basic competencies like really understanding deviation investigations, validation protocols, and the potential impacts of equipment modification.

"A quality system really serves to keep a system in a state of control. It will not fundamentally take a system that is out of control, and by pushing a button called 'quality systems' bring it back into control," said Bowles. "That has to be done manually as we start up plants and processes. We typically operate them in manual mode, and when they're close to a steady state or a set point, we push a button that engages an automatic controller. I'm an engineer by training, and that's how I see a quality system."

So the task at hand was to not only build the quality system, but also to improve basic capabilities enough to launch the system, all while the company was suffering under the onerous consent decree, which slowed production and, Bowles said, "created a huge amount of tension."

Fred Hassan, who replaced Richard Kogan as CEO in 2003, set the tone for the culture change.

"His mantra was to earn trust every day," Bowles said. "That really resonated deeply with us because … we felt from the start that the consent decree meant we had lost the trust of the FDA."

FDA didn't view it that way, even though it made perfect sense to Schering-Plough's people. They saw that "FDA required a court-ordered quality improvement plan to move forward and didn't believe that the company's voluntary improvement efforts would be sufficient. I call that trust."

This was the key to change. "We were able to capitalize on this vision of earning trust every day by just focusing on earning the trust of regulators. And earning the trust of regulators meant achieving all of the requirements of the consent decree on time. So it was just a very simple connection to the vision of the company and the requirements of the consent decree, and then we were able to create our own mantra around that internally about what we were trying to do," Bowles explained.

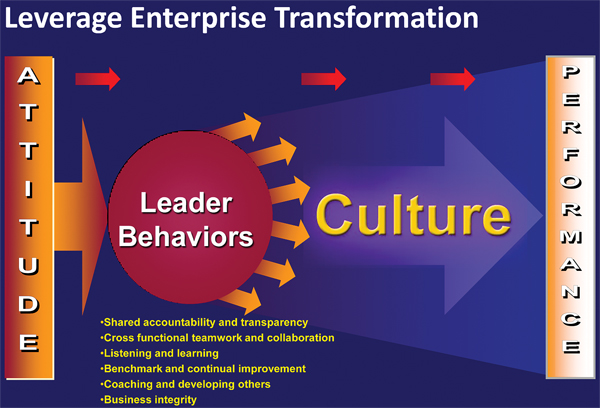

Leader behaviors

Schering's transformational model focused on what the company called leader behaviors. Schering had six of them:

- Shared accountability and transparency;

- Cross-functional teamwork and collaboration;

- Listening and learning;

- Benchmarking and continual improvement;

- Coaching and developing others; and

- Business integrity.

The leader behaviors "speak to the ideal being, if you will, in the company – that person we all aspire to be in terms of our interactions with each other."

The model Schering used, which Bowles said is well accepted in organizational development theory, is that behavior creates culture and culture then drives performance.

"I was somewhat skeptical about leader behaviors as a focal point, because it seemed to me that you could fake it for a pretty long time. If someone tells me that I have to act according to these six values, I can sort of dial them in and go to work and act that way," Bowles said. "Well, it turns out you can't hold your breath that long."

Schering used "leader behaviors" to transform its quality culture

Source: Merck

Bowles explained to "The Gold Sheet" that because organizations follow the behaviors of their leaders, "a consistent pattern of behaviors exhibited by organization leadership cascade throughout the organization and, over time, determine organization culture."

But for it to work, the leaders must show integrity and accountability in demonstrating the behaviors, he said. He added that the organization must also assess leader behaviors in key systems such as salary administration, performance assessment, recognition and rewards, and advancement.

"Without a credible connection between these organization systems and the leader behaviors, there is little leverage for culture change; indeed, organizational skepticism and employee disengagement can occur without alignment when leadership does not practice and reward the desired behaviors," he told "The Gold Sheet."

"At Schering-Plough, an extraordinary job was done by the CEO in integrating the behaviors with the key organization systems – they became real."

Connecting with corporate values

Schering also established a set of aspirational values. Bowles said different companies emphasize different values, and it's worth noting which ones they use – and which ones they don't.

"If we create quality standards within the company, they have to resonate with those values. If they don't, if a company is highly empowered, and their goal is to be highly empowered, highly directive quality standards will not resonate with those values, and therefore will not survive. So I think it's really essential that when we develop these tools and techniques, we think about the culture we're trying to embed them in. On the other hand, if the culture is very directive, is very top-down managed, is very command and control, military-like standards may work."

For its cultural quality transformation, Schering focused on four values:

- increased organizational capability;

- senior management involvement and governance;

- establishing a culture of continual improvement; and

- implementing a quality systems framework that's based on continual improvement.

He said the continual improvement mindset does not come easily to American companies, where people normally think in terms of running projects and solving problems. "A mindset of continual improvement is that there are always problems to solve and we just have to organize them in terms of priority."

The path to commitment

"The transformation took us from grudging compliance before the consent decree to an organization that was deeply committed at the end," Bowles said, referencing a "ladder of commitment" slide.

David Chesney of later commented on that slide, which showed a four-step process from grudging compliance, "I will do if I must," to compliance, "I will obey the rules," to support, "I will support the effort," and finally to commitment, "I stand for this."

Chesney was responding to a question about how to achieve quality culture change. This is something he has seen up close: Parexel is one of a handful of consulting firms that corporate lawyers call when their companies run into trouble with FDA over GMP compliance. The consulting firms then must help the clients climb that quality ladder, sometimes while operating under a consent decree.

Chesney said he'd heard the four stages expressed in a similar way – "going from denial to resistance to exploration and then to commitment."

"Having worked through problematic situations with a lot of clients over the years," he said, "it's kind of become my motto that when the resistance starts, take heart because they've moved out of denial."

He added that each stage requires a different approach. "As you're implementing a culture change activity, there are different active measures that you can do at each of those stages that helps keep the motion going forward along that continuum by however those stages are defined."

Closing culture gaps on 'Manufactria Island'

Juan Andres, the Novartis Group quality head at Novartis AG, described a similar, though broader staged approach to quality culture change.

Whereas Chesney was talking about post-crisis cultural transitions, Andres discussed an approach that also could use quality systems to rescue backsliding cultures before they slip into a crisis.

He used an analogy to the automobile industry. In the old days, you'd know you had a problem when the radiator blew. Now "we are used to having cars that tell us problems before they actually happen – and this transformation has occurred in just a few years."

This transformation, he said, "happened in the moment in which the car industry was most challenged. And they decided to go for quality and it made a big, big difference there."

He said that today, pharmaceutical quality is all about responding to breakdowns, but in the future, it will be about preventing them using Q10 quality systems to achieve competitive advantage.

The quality system should be attacking the many minor issues at the base of the problem pyramid to preempt the big problems that can arise at its peak.

He showed a five-level pyramid with non-quality-focused behaviors at the base, then deviations, critical deviations/complaints, batch rejections, and at the top, recalls.

"I remember a few months ago visiting one of the plants," Andres said. "Their focus was to find more issues at the bottom of the pyramid. And it's the first time that I saw that approach, and we're starting to try to get that thinking along some other plants. Most of the management attention tends to be along the top, with the recalls, with the events, the critical deviations, rather than attacking the base."

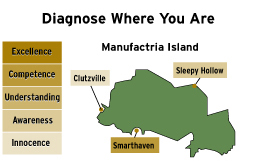

Andres went on to describe a quality culture maturity model that Novartis is beginning to use in diagnosing and treating cultural barriers to quality.

The only way to raise a poor quality culture to a quality systems approach is in a stepwise fashion, he said, explaining that "I had some trouble describing quality systems to people that don't have the quality culture. That is the real challenge."

He defined five stages of quality culture. In descending order, they are:

- Excellence – competitive advantage through prevention of all quality issues;

- Competence – quality mindset in all functions, design quality in and anticipate issues;

- Understanding – quality systems and metrics reveal reality, and drive action;

- Awareness – quality unit will identify the issues; and

- Innocence – quality mainly outsourced to regulators.

Once a company has identified its quality culture's stage, it can develop an appropriate quality plan for advancing up the quality hierarchy.

However, Andres said, it's not so simple. No company is at the same stage throughout. "You have many different manufacturing sites, many different operations, many different development units that would be in different stages of that ladder," he said.

"The situation is very dynamic. Even at sites or areas that have been high on the ladder, they tend to go down. There is a tremendous amount of evolution, you start outsourcing operations, you go to third-party contractors. The key thing is to start diagnosing where you are."

He illustrated his point with a slide depicting an island called Manufactria that has plants in three towns: Klutzville, Sleepy Hollow and Smarthaven.

"The key thing here is to diagnose specifically each one of those operations and put plans, specific plans that are consistent with that state of evolution to get into the next level."

For example, he said, "going from innocence to awareness requires a completely different set of actions than when you are higher on the ladder of quality culture."

He emphasized that "the important thing is to be very, very specific and formalized on some of those actions. … And then have the patience and the knowledge and the awareness that evolving the quality culture takes time."

The key to raising quality culture, which can vary by site, is first to diagnose it, says Juan Andres of Novartis. How does your quality culture compare? Rate it here and see![]() .

.

Raising culture through governance

Andres said the key to imbuing quality culture throughout a manufacturer and its suppliers is "to incorporate the quality culture into the governance."

Typically when companies like Novartis create their annual quality plans, they review the data from metrics, key quality indicators and corrective and preventive actions that each site or business unit generated over the previous year, assess the associated quality risk and put together a quality plan for it, Andres noted.

"My argument here is you need to take your culture, your situation with your culture, together with the data that all of this provides, and put together your annual quality plan in every single operation."

Companies should tailor these plans to the cultural maturity of each site or business unit and get the managers and quality managers of each site or business unit to approve them, Andres said.

It is especially important to develop the annual quality plan in parallel with the budget process, he said, "because you want to have the conversation associated with how you're going to be funding a lot of the things that you identify in your quality plan."

Sandoz CEO talks the talk

Jeff George, global head of Sandoz International GMBH, wowed the audience of quality professionals with his articulate explanation of how Novartis' generics subsidiary is approaching quality.

In 2008, Daniel Vasella, then Novartis CEO, asked George to take the reins at Sandoz to turn around commercial operations after a period of rather flat growth globally and decline in the U.S., "and so that was really my focus, replacing six of seven region heads, two of three business unit heads," George said.

But there were some recalls at Sandoz's plants in Boucherville, Canada, and Wilson, N.C., that year. And that August, the company's U.S. subsidiary received an FDA warning letter about GMP issues at the Wilson, N.C., plant, which eventually led George to replace the head of his U.S. operation with former Barr Laboratories CEO Christine Mundkur, who had a background in regulatory affairs (Also see "Drug Recall Totals for 2008 Highlight Global Outsourcing and Other Risks" - Pink Sheet, 1 Mar, 2009.).

At first, he said, "We really focused on driving growth and driving performance because that was what was most broken, at least in my perception. And then I started to see recalls and other issues, and I said, 'look, if we don't focus on quality as our No. 1 priority, forget about growth. This is the top priority. It was a mindset shift I think a couple years ago, probably 18 months, 24 months ago that I went through, in realizing I've got to spend most of my time on quality, development and manufacturing."

But George said that, like most people with a business background, he "initially felt intimidated by quality."

"Therefore I made a concerted effort to spend a heck of a lot of time in quality," he said. At every weekly and monthly executive committee meeting at Sandoz, "we start with quality, and we spend more time on that than any other topic."

Given the expectation that generics quality must match that of innovator products that generate much greater revenues, and the competitive reality that others will move in if quality problems keep Sandoz from supplying a product, "it's critical that we focus on quality every day for competitive reasons," George said.

He also took the position that investing in quality makes sense from a cost perspective. Despite the near-term financial impact, George anticipates mid- to long-term benefits in reduced waste, higher efficiency and yield improvements. "To me, high quality can also mean low cost."

He went through some of the things Sandoz does to ensure quality. A quality leadership council meets every month, chaired by Sandoz' head of quality, Matthias Pohl. Quality is a peer to other organizations at Sandoz. There is top-down guidance based on ICH Q10, there are significantly clarified escalation procedures, and there's lots of training.

There are also a lot of new people in charge. "We've replaced a lot of our site heads and brought in people who have quality backgrounds, and both quality and operations backgrounds," George said.

Sites must perform gap analyses and say what improvements and remediation they need. These needs go into annual quality plans, which integrate with Sandoz' budgeting process. "And in the past 18 months, we've literally committed hundreds of millions of dollars to quality systems upgrades, to capital expansion for quality reasons," an investment he attributes to the quality planning process that Andres and his team at Novartis put in place.

Sandoz tracks metrics and KQIs, George said. "I've realized the importance of focusing on the bottom of the pyramid, going to the heart of the root causes, really diving in deep with the team to understand 'why do we have this deviation backlog? What are we doing about it from a CAPA perspective?'"

Sandoz is adding resources to audit its 400-plus third-party contractors and 1,000-plus suppliers "to ensure that we're tracking and catching issues earlier in the process and that we're helping and partnering with our suppliers to raise their standards of quality systems."

He highlighted his decision to co-locate manufacturing, development and quality at headquarters and, as much as possible, at sites, "so that we improved the interaction, so that we're putting product quality first every day, so that our tech transfer process from development to manufacturing is robust, and so that we're continuously supporting a robust manufacturing and quality system."

The company is shifting from the fire-fighting mode to "I guess what Q10 calls feed forward," and the sites have been working to share what they learn.

George works to promote culture change with his blog posts and a quarterly newsletter that goes to all 24,000 Sandoz associates around the world. The company aims to "embed quality objectives into every associate' objectives," but particularly focusing on "driving behavior at the shop floor level."

"It's not just about quality behaviors," George said. "It's about making that habit and making it ingrained in the DNA of our Sandoz line employees that are working every day producing products."

All this and a warning letter too

During the discussion after George's talk, leading quality professionals gushed with praise.

Neil Wilkinson, who was, like Novartis' Andres, on the program planning committee, and is a partner in the consulting and training firm NSF-DBA, said, "I don't think I have seen so far a presentation by a senior leader from a non-quality background on this topic articulate things so well. I've seen other leaders give it, but they're clearly delivering other peoples' overheads and struggling with some of the content. So that's absolutely fantastic. … Quality at the top of the agenda for senior management meetings is also incredible."

Parexel's Chesney, who was moderating the discussion, noted that after posing a written question, one attendee had scrawled on the card, "Let me know if Matthias leaves," a reference to George's head of global quality assurance.

"So I think Jeff you've impressed everyone," Chesney said, "and if you have a vacancy, you're going to get 200 CVs from this room."

And yet, just six weeks later, FDA sent Novartis CEO Joseph Jimenez a warning letter![]() about GMP problems found during inspections over the spring and summer at three Sandoz plants, including many repeat observations from the 2008 warning letter.

about GMP problems found during inspections over the spring and summer at three Sandoz plants, including many repeat observations from the 2008 warning letter.

The Nov. 18 warning letter concluded with this stinger: "Finally, the agency is concerned about the response of Novartis to this matter. Corporate management has the responsibility to ensure the quality, safety and integrity of its products. Neither upper management at Novartis nor at Sandoz Inc., nor at Sandoz Canada Inc., ensured global, adequate or timely resolution of the issues at these sites."

It turns out that all is not yet well on Manufactria Island.